Intro

“Men of Egypt! Women and children…

Here, before the whole world, is a living symbol of your will, power, persistence, work capacity, and sacrifice.

Here, this High Dam, is a victory souvenir over all obstacles.

Here is a clear picture of your dreams, realized by the mighty work which subordinates nature, regardless of price in blood and sweat, to assert man’s determination, with God’s spirit and guidance, to honor, and be honored, by life. Friends, citizens, no spot in the world materializes the great struggle of the contemporary Arab, in its full scope, as this site on which we stand, the site of the Aswan High Dam.

Here, the political, social, national, and military battles of the Egyptian people materialize as the bulk of the great rock which blocked the old Nile waterway, to accumulate its waters into the biggest lake ever made by man, as a permanent source of prosperity.”

Extract from Gamal Abdel Nasser’s the speech on the occasion of the diversion of the Nile River, 14th May 1964

History/Background

In 1964 newly cultivated settlements in the desert north of Aswan were arranged to house the Egyptian Nubians after a massive relocation campaign that was part of the construction of the Aswan High Dam and behind it the ‘biggest lake ever made by man’. However, despite the fact that the Nubian community was “compensated” for the loss of its land on the banks of the Nile River, this loss could not be materially indemnified. The relocation of the community by the state did not only lead to the loss of land but also to a struggle for the community’s identity and culture. By relocating the Nubians away from the Nile and out of their villages their camaraderie and sense of community were deeply affected. Songs that were sung after the resettlement tell stories of the Nile and express a deep yearning for the flooded homeland. At the same time, some of the Nubians perceived their loss as a contribution to the common good of all Egyptians, and prayed that the Nile would be as good to Nasser as it has been to them.

The preparations for the Aswan High Dam construction site constituted a budget of 5 million Egyptian pounds and entailed the extension of the Nile Valley railway line, the construction of a power connector to the power plant of the Aswan Old Dam as well as workshops and workers’ settlements with their associated infrastructure. However, the dam that promoted an egalitarian society and national unity did not reflect that on an urban scale. Engineers, foreign experts and technicians lived in well-built compounds and were offered a wide range of facilities and services while the laborers and builders lived in informal shacks and tents. Forty-three years after the completion of the dam, the workers’ settlements still exist and have developed into multiple quarters. The old construction site workshops are left unused.

Project description

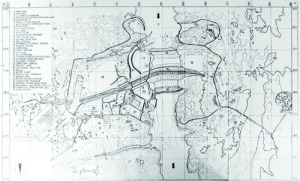

The following proposal explores the Aswan High Dam as a mega-project of a previous era, a piece of infrastructure of great national and geopolitical significance that once promised a new futures for the nation, for society and for the nation’s refashioned subjects. This monumental structure, which altered the Nile River’s ecosystem and landscape, as well as Egypt’s agriculture and energy supply, also triggered through its insertion a widely overlooked process of urban development – one that this study unravels. The research presents a retroactive reflection on the construction plan of the dam and puts forward the hypothesis that this plan – in fact – led to the unforeseen creation of a new city, the City of the High Dam. Following an on-site investigation of the geographical, urban and architectural parameters surrounding the dam, the proposal translates the findings into a history of creation of the “City of the High Dam” from 1944 until today and imagines a vision for this – fictional on paper, but very much existing – city in 2064, one hundred years after the dam’s construction.

The built environment in the immediate vicinity of the Aswan High Dam today is an agglomeration of districts of different characters and functions. Roads that are kilometers long cut through granite deserts connecting industrial and residential areas as well as educational facilities, landmarks and touristic temples. Electrical transmission towers dominate the landscape. The last Nile Valley railway station is located on the eastern riverbank overlooking Lake Nasser and the harbor – which together with a weekly ferry constitute the only connection to Wadi Halfa, the next city on the Sudanese border.

The presented design considers existing functions in the city as an archipelago and attempts to link them and complement them with places of gathering and public functions that were the main components of every old Nubian village and community. It proposes alternative solutions to perceive the dam – the reason for the city’s existence and its main resource – as part of the urban fabric and consequently to create a city center around it.

How can loose agglomerations of infrastructural, residential and administrative buildings amount to a whole, complete and connected city? What are the limitations of design in a location of great social, political and economic complexities? How could this city evolve 100 years after the completion of the dam? Is it possible to revive traces of a lost community? And, how can the City of the High Dam reach its full potential of becoming an important port city at the end of the Egyptian Nile Valley and a gateway to Africa?

The Aswan High Dam Authority owns most of the land surrounding the dam, and is responsible for its maintenance and security. Therefore, the complete area is spatially controlled by a number of political and security measures around the dam dictated and shaped the ways in which the nearby urban settlement developed:

1. A dividing line between the two riverbanks for 12 hours of the day, where the dam is inaccessible to cars and pedestrians (from 5:30 pm to 06:00 am).

2. A 1 km safety radius around the dam where no boats are allowed to come near the structure.

3. A derelict granite quarry that is meant to become a granite reserve for the dam.

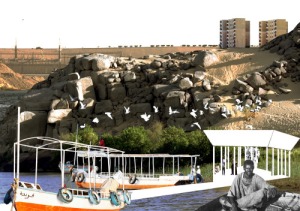

In the past, these security measures have limited the development of the city. The proposed project however, looks at them today as areas of potential urban and architectural interventions of different scales in the city. The first intervention is planning a public transport system, composed of the existing train line connecting the city to Aswan, a new bus as well as ferryboat network and a cable car line. This transport system allows the process of city formation that had started 40 years ago to develop further, faster and in a more purposeful way. The newly inserted bus, ferry and cable car stations embody starting points for the creation of new quarters, and designing these stations and how they interact with the existing sites on different scales constitute the second intervention of this project. Furthermore, the stations are designed to become meeting points and transit hubs that would restore a lost community spirit. The cable car stations are placed at the highest points of the city whereas the ferryboat stations are located very close to the Nile and its immediate landscape. The bus stations on the roads offer fleeting views of the different city districts, which make it possible to fully experience the entire city through its public transport.

The cable car line is an attempt to work against the dividing line that intersects the city, and makes it possible for the two riverbanks to be connected throughout the entire day. The site of the cable car station on the eastern riverbank was chosen along the promenade, which is informally used today by workers as a place of gathering after a hard day at work to watch the Nile water flow through the turbines of the hydropower station at sunset. Its insertion would enhance the flow of people to this site, which offers a breathtaking view over the dam and the Aswan reservoir. The promenade would become a linear market, where the vendors could sell vegetables and fruits as well as Sudanese goods that arrive regularly at the harbor. The cable car reaches the other side of the river at a station at the derelict granite quarry, which would trigger the development of a new residential and cultural district – the “Granite Quarter”. This would be the closest quarter to the dam, and therefore together with the promenade, the new city center. The landscape of the quarry is to be used to host a new small amphitheater.

The new Aswan Reservoir ferryboat line would connect the islands in the reservoir to the new city center. In addition, the Lake Nasser ferryboat line is designed to make the touristic sites and temples, i.e. Kalabsha Tempel and Abu Simbel, publicly accessible and to enhance the use of the lake as a public recreational area.

The bus stops are located along the existing roads and residential districts and near existing institutional facilities, such as the post office, the school, the Aswan University campus and dormitory, the Aswan International Airport, the harbor and the Aswan High Dam Authority. The bus lines are linked with the new ferryboat and cable car stations and lines, leading to an interconnected and efficient transportation system. By changing the mode of transport multiple times within one commute, the city becomes easily readable for inhabitants as well as visitors. The stations and the spaces they define are meant to be reminders of the market places in the old Nubian villages. Depending on the their scale and location they shape spaces where different patterns of activities and encounters can take place; from having a cup of tea while waiting for the bus to playing a game of backgammon at the ferry station and trading goods near the cable car station. Unlike traditional urban sprawl, where cities grow towards their peripheries, the proposed interventions aim that the city of the High Dam would grow inward toward the dam. By 2064, High Dam City would still be governed by the Aswan High Dam Authority. Reviving the spirit of the old Nubian villages, the city would be self-sustainable and would not be based on private land ownership. The city could then be fully experienced through its transport network and would have a well-developed city center. The inhabitants could experience their city on their daily commute to work, school or university from different viewpoints and at varying speeds. The dam would no longer be an alien infrastructural body dividing the city but rather a palimpsest of the city’s own history, a city landmark and a place of gathering.

Conclusion

The project intends to reveal the rich history of this location and emphasizes its specific cultural identity. Moreover, it provokes a discussion about the boundaries of visionary urbanism and how it stands in contrast to notions of Utopia. Rather than (consciously) criticizing past political and infrastructural decisions, this project’s contribution lies in using visionary urbanism as a tool to criticize the limits of reality as accepted by planners today and seeks to visually project the “still possible”.

In the light of the anticipated development of the New Suez Canal Project, again questions about the process of planning big scale infrastructural projects in Egypt must be raised. The Suez Canal Corridor Development Project is the latest announced project in a series of ambitious development plans since the 1950s. These projects—triggered by the government’s fervor of mega projects as a solution for Egypt’s demographic and economic problems—become the government’s publicly hyped attempts to distract from daily economic and political problems through promoting a strategy of ‘we plan, we build, we deliver’. However, often what is promised to be delivered—if it ever reaches such stage (note: Toshka, among many others)—also leads to major unplanned urban and social changes that take place beyond the drilling and excavation work and continue to develop for years after the project’s completion. The discrepancy of abstract visions of political leaders and the urban situations they impact in reality has an immense effect on Egyptian cities and their residents, which raises questions about the role of military planning today: In a city like “High Dam City” or even the “New City of Toshka” where militarized zones of exception proliferate, what/who then defines the city? Who plans its city center, public spaces and transport systems? Is there a way around individual and communal sacrifices of land for the “common national good”? And will history repeat itself in the cities of the Suez Canal Zone?

Alia Mortada received her Bachelor and Master in Architecture from RWTH Aachen University, Germany. Her current research examines the effects of national mega-projects on Egyptian cities and communities.